|

|||||||

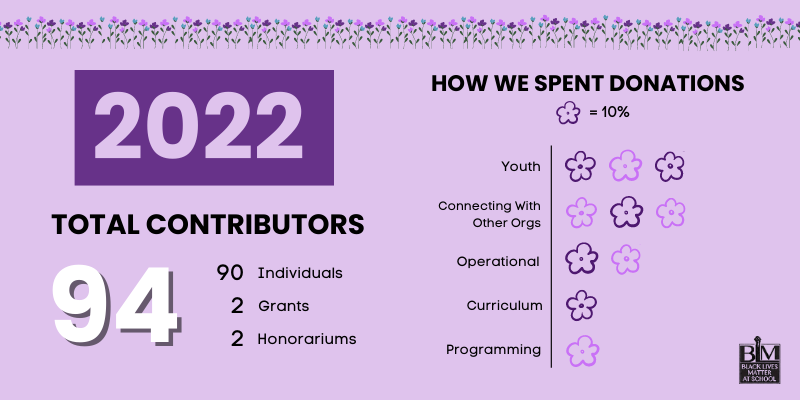

| 2022 Annual Report Here | |

| File Size: | 1884 kb |

| File Type: | |

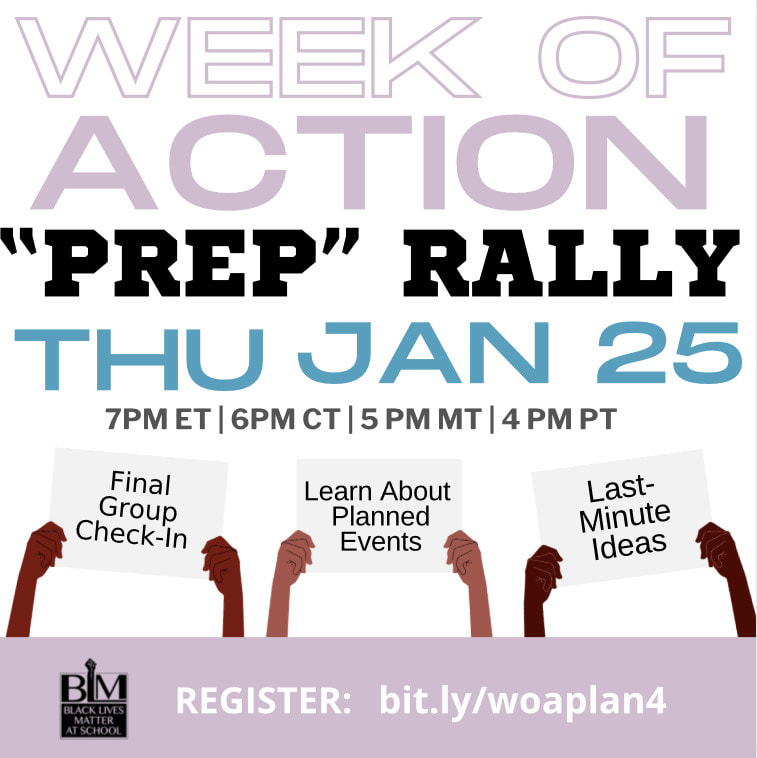

Prepare for the 2023 Week of Action! Attend the 2023 Black Lives Matter at School Curriculum Fair.

12/19/2022

Saturday, January 21

11:30am - 2:30pm ET

8:30am - 11:30am PT

Annual fair designed to uplift the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands of Black Lives Matter at School. Online.

Hosted By - D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice

Register - Mobile eTicket

About

Register today for the annual D.C. Area Black Lives Matter at School Curriculum Fair, hosted by Teaching for Change's D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice (DCAESJ). This online event is open to all educators, not just those in the D.C. area, with the purpose to prepare educators for the National Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and Year of Purpose. Learn from and collaborate with educators in workshops designed to uplift the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands of Black Lives Matter at School. Additional information to be announced. Read about the 2022 fair here!

Curriculum Workshop Proposals

DCAESJ is seeking workshop proposals for the curriculum fair that speak to the National Black Lives Matter at School Year of Purpose, centering the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands in the classroom. Applications will be accepted on a rolling basis until Tuesday, January 3. More Info

SUBMIT YOUR WORKSHOP PROPOSAL

11:30am - 2:30pm ET

8:30am - 11:30am PT

Annual fair designed to uplift the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands of Black Lives Matter at School. Online.

Hosted By - D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice

Register - Mobile eTicket

About

Register today for the annual D.C. Area Black Lives Matter at School Curriculum Fair, hosted by Teaching for Change's D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice (DCAESJ). This online event is open to all educators, not just those in the D.C. area, with the purpose to prepare educators for the National Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and Year of Purpose. Learn from and collaborate with educators in workshops designed to uplift the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands of Black Lives Matter at School. Additional information to be announced. Read about the 2022 fair here!

Curriculum Workshop Proposals

DCAESJ is seeking workshop proposals for the curriculum fair that speak to the National Black Lives Matter at School Year of Purpose, centering the 13 Guiding Principles and national demands in the classroom. Applications will be accepted on a rolling basis until Tuesday, January 3. More Info

SUBMIT YOUR WORKSHOP PROPOSAL

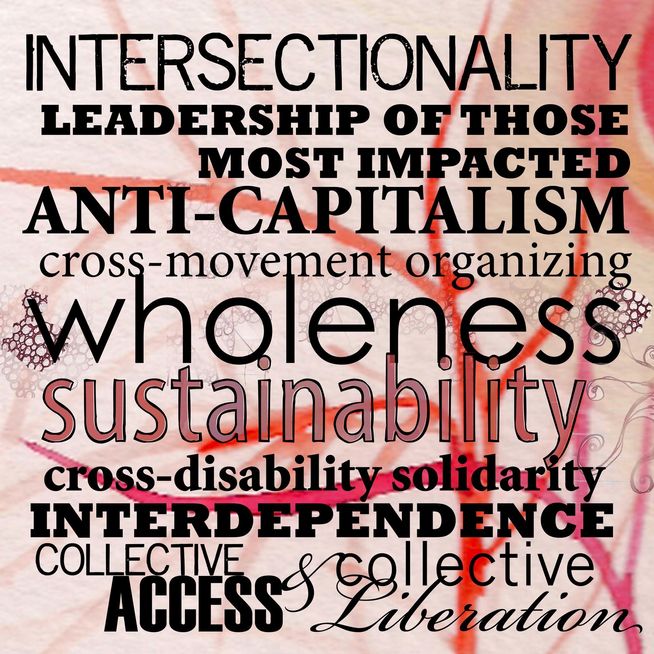

To fight against societal ableism, we must celebrate our differences and understand how the lessons from Black disabled organizers teach us how to build inclusive, accessible movements. Uplift the principles of globalism and collective value by incorporating the following resources into education spaces and personal practices.

Get monthly updates. Subscribe to our

newsletter.

Archives

February 2024

January 2024

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

July 2022

May 2021

March 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed